Corporate Aliens: Centralized Admin Teams

At previous companies, I learned quickly to minimize contact with the "mothership" as much possible. The mothership was a constellation of central teams--HR, legal, brand police--that seemed to be from another planet. They said they were here to help, but every interaction seemed frustrating, slow, and full of "mandates" that did nothing to help me ship the next feature, complete a report, or otherwise hit my target. Their perspective were so different, they often did seem like aliens.

Yet, at Extra, we're not only a fast-growing startup, but also a fintech with a large marketing effort. We absolutely have to get things right when it comes to people practices, compliances, and brand. It's critical that we bridge this gap between centralized admin teams and the operating teams...somehow.

I'm actually hoping that we can do better than I've experienced anywhere else.

The first step is to help our operating teams understand where these admin teams are coming from. The HR/legal/brand decision-making perspective comes from the intersection of three concepts:

- Binary Outcomes

- Risk of Ruin

- Actuarial View of Risk

Once you understand these and how they interact, you'll understand exactly why these teams emphasize what they do and are generally so conservative--often in ways that feel designed to ruin the day-to-day lives of operating teams (though nothing is farther from the truth).

Binary Outcomes

Binary outcomes describe situations where either A or B happen, but not both--and there's no shades of grey in between. Examples:

- A coin flip lands as heads or tails

- The Rams either won the Super Bowl or didn't

- You got the job or didn't

- You either got into a car accident or managed to swerve just enough

- A gazelle either escaped the pouncing lion or was eaten

- You got sued or didn't

- You had a giant negative press event or didn't

Notice that there's a mix of good, bad, and neutral examples. Defining something as a binary outcome doesn't also define if the outcomes are positive, negative, or indifferent--just that there are only two options and one of those will happen. They don't 10% happen or 70% happen, they either do or they don't (i.e., can't be a little bit pregnant).

There's another major property of binary outcomes: probabilities of outcomes aren't very useful when things happen only very infrequently (or even just once).

You might guess (beforehand) that Russia had a 10% chance of invading Ukraine and No Invasion had a 90% chance--but after the invasion started, how do you know if you got unlucky or your judgement of the odds was wrong?

The short answer is: you can't. The only way to know the "real" odds is to repeatedly run the same experiment and see what you get (which you can do for coin flips and absolutely cannot do for invasions).

And even that is problematic--we assume there's a 50/50 chance for heads and tails because who would mess with every coin ever made? But what if the particular coin that's going to be flipped doesn't have an equal chance of heads and tails--can you imagine having to distrust that at every turn? And that's for a "simple" thing like a coin flip, good luck when we get to real-world events.

This leaves you mathematically adrift. You can't judge real probabilities, so it's very hard to judge how aggressively to invest in profiting from or protecting against a given outcome.

Worse, you can't try to "outsmart" the odds even when you do get repeated tries at the decision. For example, in hiring, you may learned that X% of the employees just won't work out, and one in 1,000 of those will turn around and sue you. But those are the odds after using every resource at your disposal to avoid the bad outcomes.

You can't use the existence of the safety protocols as an excuse to ignore the odds--and once the safety protocols are in place, you can't pretend you know which hires are likely to turn into trouble. If you could figure that out beforehand, whatever method you were using would be part of the protocol!

So you have to accept, at some point, you just can't know how things are going to play out.

Risk of Ruin

The second major concept, "risk of ruin" is a really common concept in trading and gambling. It's the odds that a given strategy will lead to a total loss of your bankroll, so you're knocked out of the game ("ruined"). In more general settings, I think of ruin as a loss that's so big, your only new goal will be getting back to where you were.

Other forms of ruin:

- Divorce

- Getting fired

- Bankruptcy

- Major car accident or other injury

- Getting sued

- Death

Notice that the above isn't necessarily about hitting a milestone that ends the game. It's enough for the setback to sufficiently bad that the new goal becomes working back to where you were before the loss.

Whenever the risk of ruin is present, you have to give it more weight than it otherwise deserves based on probability or the absolute size of the loss.

The simplest example of this is Russian roulette. Let's say I gave you a revolver with 6 chambers, only 1 loaded. If you pull the trigger, I give you $10M. Do you take the bet?

Well, the expected value of the bet is ( 83.3% * $10M ) - ( 16.7% * DEATH )= ???

I don't know. That math looks a bit harder than expected. That what risk of ruin does.

Actuarial View of Risk

The third and final concept relates to the way risk sums up over time.

Most of us, when we think of risk, think of the odds of various outcomes for a single decision, taken in isolation. Our mental models are as if we're playing a pretty normal game of roulette (let's call it Casino Roulette):

- You can bet on:

- Black (18 out of 38 spaces), pays 2 to 1

- Red (18 out of 38 spaces), pays 2 to 1

- Green (2 out of 38 spaces), pays 36 to 1

- You only make one bet at a time

- If you guess right, you get the payout

- If you guess wrong, you can only lose what you put on the table

- The rest of your bankroll is safe

- You can quit at any time, and you'll probably only place a few bets

When playing Casino Roulette, you can safely ignore things that sufficiently unlikely (like green), because you most often get away with dismissing such a small probability. If you do get unlucky, you only lose that one bet--so just play through. No big deal.

However, life is more like a different, weird version of roulette (let's call it Biren's Roulette):

- You can bet on:

- Black (18 out of 38 spaces), pays 1000 to 1

- Red (18 out of 38 spaces), pays 100 to 1

- But if the ball lands on Green (2 out of 38 spaces), you lose your entire bankroll, even if you didn't bet it (i.e., "ruin")

- You only make one bet at a time

- Once you start betting, you can't quit until you've made at least 60 bets

Even with the crazy payout table, it's really that last rule in Biren's Roulette that poses the problem. The odds of hitting green on any single spin are pretty low (about 5%), so your odds of not hitting green are high (95%). If you had $100, you could bet $10 on black up to ten times and probably walk away happy after winning once or twice.

However, that doesn't tell the story when you're forced to spin the wheel 60 times. The odds of not hitting green on a single spin remain unchanged, but the odds of not hitting green get smaller with each additional spin. It's calculated as the odds of not hitting green on spin 1 * the odds of not hitting green on spin 2, etc.

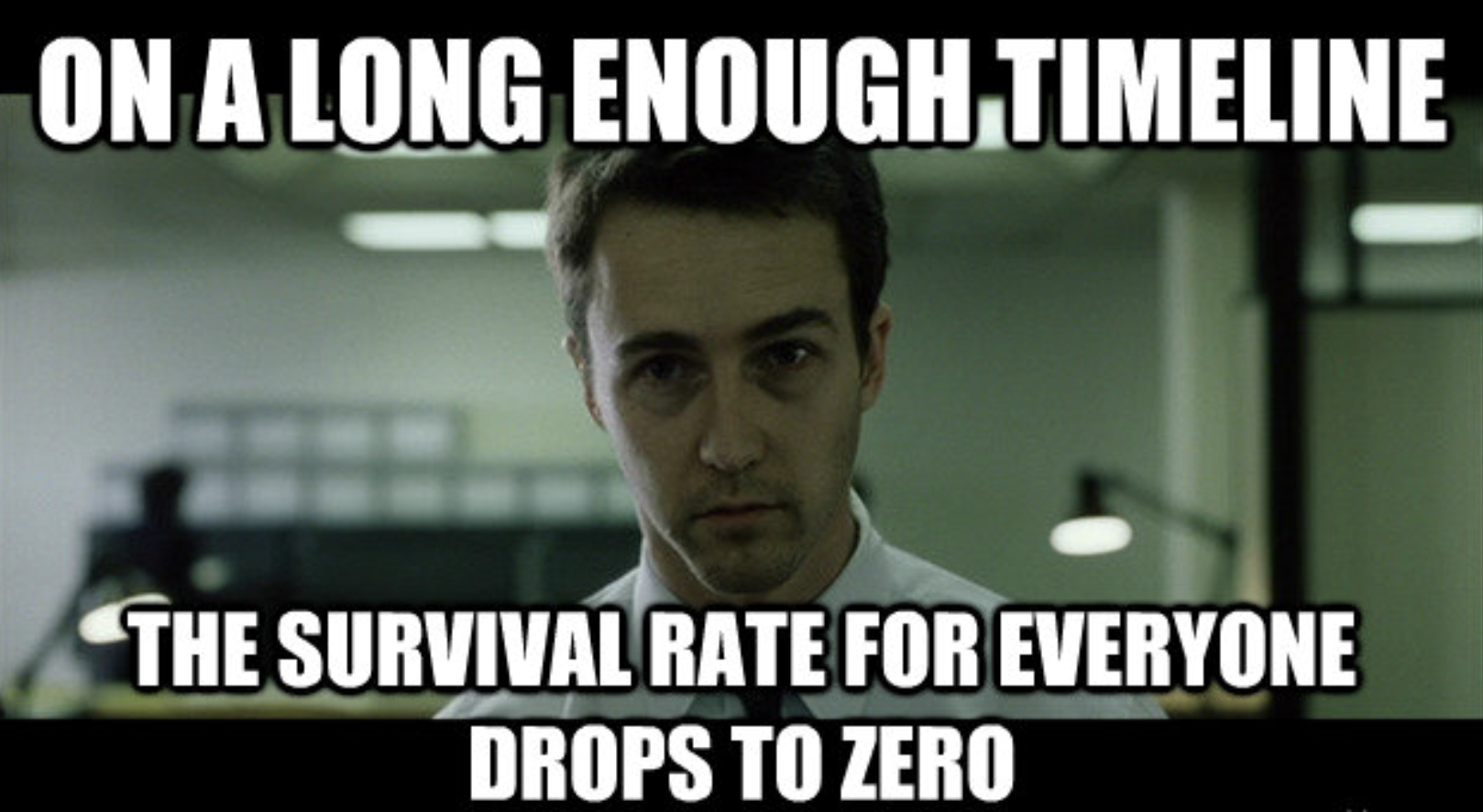

By the time you get to 20 spins, the odds of not hitting green have fallen to 33%. By the time you get to 55 spins the odds of not hitting green have fallen to just 5%. So the odds of not hitting green across 55 spins are just as low as the odds of hitting green on just 1 spin. By forcing you to bet 60 times if you bet once, I'm all but guaranteeing you're going to hit green once, lose all your money, and end the game there.

Weird, right?

This is what I call an actuarial view of risk. Risk adds up across number of "bets". Something that is very unlikely to occur on any single bet becomes very likely to occur at least once if you make enough bets.

If the outcome of that occurrence is "ruin", then the inescapable implication of playing Biren's Roulette is clear:

Understanding the Aliens

Alright, so let's see what your decision making would look like when you face:

- Events with binary outcomes

- where the probabilities are nearly impossible to judge

- and there are no reliable indicators of which bet is going to be a problem vs any other

- The risk of ruin

- where if that outcome occurs, you suffer a major loss

- And an actuarial view of risk

- where you understand that even if an event is exceedingly unlikely, it's going to happen eventually if you make enough bets

At this point, I bet you're thinking I'm going to tell you that "obviously, this would make you risk averse". But no! It's not that simple.

Even when you can't judge the odds well and you face risk of ruin, sometimes the right answer is just to do the risky thing and pray for the best. Other times, it's the exact opposite. What determines the "right" decision?

The number of times you have to do it.

If you can do it just once or a few times, you often get away with just hoping you don't get unlucky. That may be the right option. Often, it's the only option. But if you have to do it many, many times--you'd be insane to not lock that risk down.

This sets up the basic conflict between centralized admin teams and the operating teams they're meant to serve.

Operating teams, by definition, need to be relatively small in order to be effective. (If you've read Communication Thresholds, you know why.) For our discussion here, an operating team is a specific group of people working to create specific output, having nothing to do with the reporting structure in the org chart. This might look like 1 product manager, two designers and a few engineers. Or it could be a particular influencer and their business contacts working to create content.

The operating teams, by and large, don't hire many people. They don't engage in many legal interactions. And they ship very few features or products with an impact on the brand. This is just a function of their small size (usually just handful of people, almost always less than 50).

But in a large company, there could be hundreds of these operating teams--each individually small, yet collectively forming a workforce of thousands of people. The admin teams, by the centralized nature, spend their days look across all the teams. The see all the hires, contracts, and brand-impacting initiatives.

Both kinds of teams can see they're playing Biren's Roulette, but for any given bet in Biren's Roulette:

- The operating team sees the bet as a one-off, having huge upside, with very minimal risk

- The central team sees the same bet as one a series of similar bets, each one incrementally increasing the risk of "green" until it inevitably happens

It's the exact same bet--the exact same events and decision. It just looks different from where you stand because of the context of your experience, which is determined by whether you're on an operating team or centralized admin team.

This is why admin teams seem like aliens to operating teams. Admin teams have context that operators don't. The operators see something that, from their perch, looks very low risk. The same thing looks like a guaranteed train wreck--just a matter of time--to the aliens, err...admin teams.