Looking Over Horizons: Public Tech Companies

Yesterday, I wrote about how the tech ecosystem is shrinking in private venture funded companies, leading to fewer jobs for tech workers. Today, let's look at the public company side.

Public tech companies make up over 30% of the S&P 500 and are generally profitable. They're so profitable that, as of September 2023, the top 13 tech companies (Apple, Microsoft, etc.) held over $1 TRILLION in cash! They're clearly in no danger of going out of business--but they've been laying of workers. What gives?

First, we have to recognize that, given their enviable positions, when these companies set their budgets, they're really deciding how much to invest in future growth vs how much capital to return to shareholders today. For the most part, CEOs of public companies make that tradeoff using a simple algorithm:

- Share price going up -> Invest more in the future

- Share price going down -> Return more capital today to prop up the share price

While there are nuances and exceptions, this lens will help you make sense of a lot of the big decisions made by large, profitable public companies.

Since the GFC, there have been two major tailwinds driving the public share prices up:

- Rising bond prices

- Corporate buybacks

Rising Bond Prices

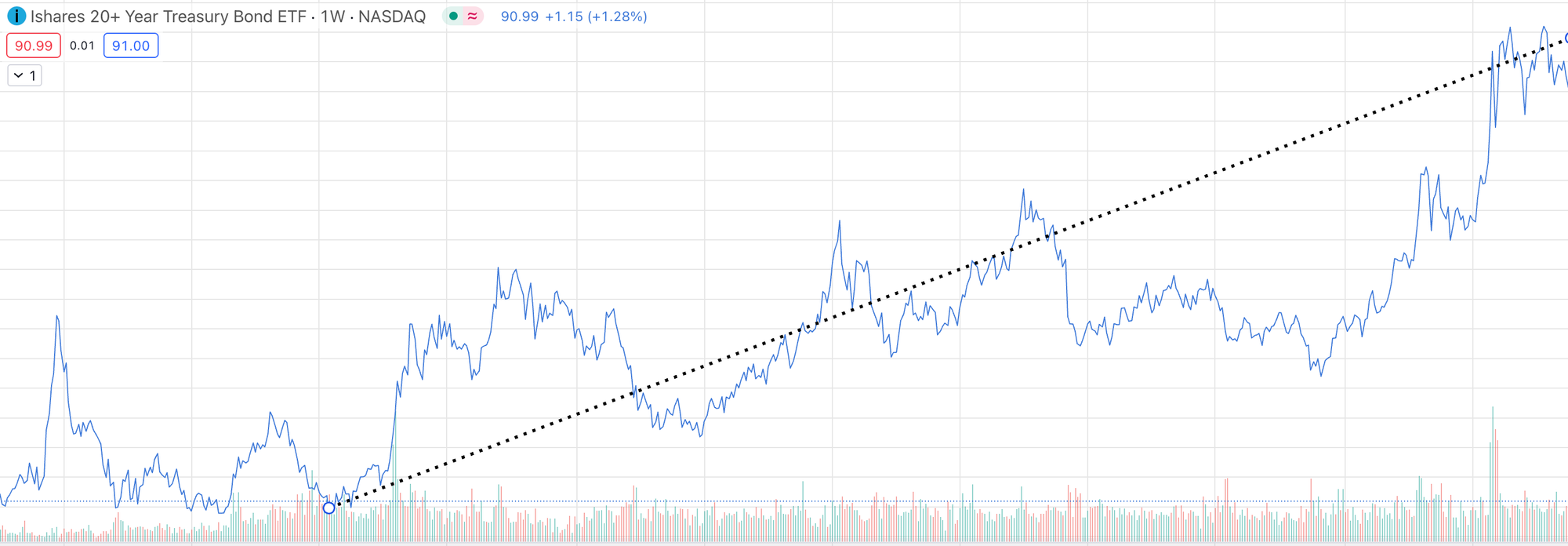

First of all, let's agree that from 2010 to the end of 2020, bonds were on a one-way trip to the moon. Here's a chart of TLT, a 20-year bond fund, over that time:

Great--how did that drive stock prices? Through target-date funds. (Much of this discussion relies on great work done by Michael W. Green.)

Target date funds are a type of retirement account where a person sets the year they plan to retire--the target date. The algorithm of the account then allocates their investment dollars across equity index funds and bond funds, slowly shifting the mix away from equities and into bonds as the target date gets closer. The allocation starts as high as 80% to equities when you're young and falls all the way down to just 25% equities when you're close to retirement.

How does that drive tech stock prices? Because the funds don't care about valuation, like at all. For simplicity, let's say your target date fund has a 50/50 allocation to stocks and bonds. If the price of the bonds go up, then you're now out of balance. The target date fund either sell some of your bond holds and buy stocks or divert future contributions towards stocks until you're caught up. In other words, when bonds go up, your target date fund buys stock!

Since these funds are now the default option for 401(k)s, nearly 60% of the $6.6T in 401(k) assets are in some kind of target-date fund. This money (not a small amount) is explicitly linking stock prices and bonds prices--something that drives stock prices marching upward as bond prices rise and vice versa.

Corporate Buybacks

It's pretty obvious that corporations support the price of their stock by buying it, just as any buyer would. There's a special dimensions to corporate buybacks though:

Corporations weren't just buying shares with profits. On net, issued debt to fund the purchase of stock through their buyback programs. This is the same as if you or I took out a HELOC to continue spending above our incomes.

When bond rates were low (and falling), this kind of made sense--or at least didn't cause too much damage. The cost of interest was just so low.

This did mean that these company's balance sheets were weakening. Of course, that doesn't stop management teams, who now make a significant fraction of their money through stock-based compensation (compensation that is only worth anything if the stock keeps going up). Who cares if we're hollowing out our balance sheet and becoming a little more fragile every quarter?

But when treasury bonds are offering 4.5% or 5%, taking on debt now costs these companies 7% or 8%--real money. The optics of hollowing out your balance sheet are worse and, if you're not Apple or Microsoft, those principal and interest payments might start causing real problems for you.

So, just as bond prices helped in two ways when they were rising (by driving funds from bonds in stocks and allowing large corporate buybacks based on cheap debt), falling bond prices hurt in two ways:

- As bond prices fall, the money starts to flow back into bonds from equities

- Falling bond prices = higher interest rates, making it harder to continue large share buyback program

Since 2020

If we look at bond performance since 2020, we see a very different picture:

The sharp drop in bond prices started at the end 2020, but it took about a year to show up in share prices (we know how 2022 turned out).

Despite markets hitting all time highs, if you're not one of the super cash-rich tech giants, your equity price hasn't recovered very well. Let's use Affirm as a stand-in for so many tech companies that crashed in 2022 and barely recovered:

Plus, your starting to worry about your cash pile + the cost of debt as you'll soon have to refinance. Share buyback programs may not look like a good idea anymore, but cutting those will put further pressure on your stock price.

If you're managing one of these companies, that pressure directly impacts your compensation--can't have that! Better to cut costs to offset rising interest expense, so you can keep buying shares.

If you're one of the tech giants, your share price has recovered (yay!), but the drop in share prices that happened in 2022 put forces in motion that can't easily be reversed:

Share price going down -> Return more capital today to prop up the share price (i.e., layoffs).

That process takes time, and we started to see a rise layoff notices in 2023 that has continued to accelerate at a faster pace in 2024.

If Twitter/X cutting 75% of its workforce and still functioning is any example, then management might find that layoffs don't hurt as much as they expected them to--though there maybe lurking quality issues growing in the new cracks form (hard to tell until something big breaks). So maybe, you're even motivated to keep cutting because the short-term results keep getting better (lower expenses) while the long-term costs (if any) are hard to measure and far off in the future.

And you don't owe interest on laid off personnel, whatever happens with bond prices...